A Final Family Reunion

Going Back Again

by Theodore Modis

Last

time I visited my hometown, Florina, ten years ago, I decided it was the last time.

Florina had changed too much and there was no one left from the people I had

known as a child. It was nothing like the first time we had visited with my

mother and Carole thirty-five years ago. Then it was my homecoming, I was

freshly married, and had just completed my long studies in the US. The three of

us had paraded the town’s main street stopping every few meters to greet

acquaintances.

“How are you, Mistress Theodosia,

welcome back,” was a frequent greeting. Having spent thirty years as a teacher

in Florina my mother was known to many as Mistress Theodosia.

“This is my son and his wife,” …

“Yes, she is American.”

“Son of George Modis! Why don’t you

come back and we’ll vote for you,” was another typical remark as we moved from

one encounter to the next. Carole had been stunned by such celebrity treatment,

which had left neither my mother nor me indifferent.

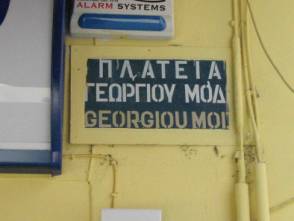

By the time we had reached the town

center – George Modis Square – the sequence of encounters culminated with an

embarrassment.

“Oh, Theodoraki, do you remember

me?” Asked a lady of my mother’s age looking at me pointedly.

There was no chance I would remember

her and the sorry event she was about to unearth from the depths of my Freudian

forgetfulness.

I must have been less than ten years old when

inspired by cowboy movies I wanted to improve my aim. I made myself a dart out

of a cylindrical piece of wood at the end of which I inserted a nail backwards

– not a trivial task for a young kid. Then I attached some chicken feathers at

the other end and was ready to show off to the other kids.

My first throw was across the street aiming at the

trunk of a tree. There was a breeze, however, which made the dart drift and get

implanted on the leg of one of the kids sitting on the sidewalk nearby. I was

shocked and so was the kid. I pulled out the dart whose nail had deeply

penetrated. The hole was tiny and seemed innocuous. But we were both in shock

so we walked into the café in front of which all this was happening and showed

the bleeding hole to the café owner.

“That’s nothing,” he decided “here, let’s put some

ouzo on it.”

Over lunch at home I was brooding.

“What is the matter?” asked my mother.

“Nothing,” I refused to say.

But she knew me better and insisted. I broke down and

told her everything. She was alarmed. A death of a friend’s kid from tetanus

had been indelibly written in her memory. She grabbed my hand and we went out

looking for the kid’s residence. With some effort we located the boy and took

him to a first-aid station for proper treatment, which included a tetanus shot.

Still a week later, the kid’s mother showed up at our

house saying that his leg had been infected and there had been doctor’s and

pharmacy bills. My mother reimbursed her for everything with apologies. I had

never seen that kid or his mother again until now.

But going back ten years ago was

different. We did not have my mother with us. She had just celebrated her 90th

birthday and was less mobile. This plus the changes Florina had undergone in

twenty-five years resulted in zero flamboyant encounters for us as we strolled

down Florina’s main street. Many new people from the surrounding villages had

moved into the town and most of the locals had moved on to Thessaloniki or

Athens. I was frustrated at not recognizing anyone so at some point I walked

into the town’s largest hardware store still under the last name of a childhood

friend and asked to speak with Christos. “Oh, Christos has become a doctor and

now lives in Thessaloniki; and who are you?”

So our visit to Florina ten years ago was less than a

memorable experience and I had concluded that after a certain time one should

no longer seek to go back. There was also something else. Without our mother

and wanting to squeeze in a daily excursion to the beautiful Prespa-lake

region, neither Agla nor I hesitated in skipping the traditional visit to my

father’s grave at the scenic cemetery of St. George in Florina’s outskirts. And

yet, it had been many years that anyone had paid respects to our father’s grave

in which my grandmother had also been buried eight years after her son died. My

mother had been disappointed at us for not passing by the cemetery to see how

the tomb was doing.

Now a new trip to Florina was

imposed on Agla and myself. My mother who died five years ago was buried at the

cemetery of Thessaloniki with the understanding that some day her remains would

be transported to Florina to be placed in the same grave as my father. The

progressively increasing rent for a grave at the busy cemetery of Thessaloniki

now reached 1000 Euro for one more year so we decided that it was time to

undertake the painful operation of finally putting our mother together with our

father. An added source of worry was the fact that the small St. George

cemetery in Florina had long been closed to public because a larger new one had

opened in the other side of town. We had heard stories of people being rejected

when they tried to do similar operations.

Agla wondered whether we should

first call to find out. But I was adamant, “I’ll talk to the bishop,” I said.

“If need be, I’ll go to see the mayor. There should be a weak spot somewhere

for the name of Modis in Florina,” and I quietly stashed away a copy of my

mother’s autobiographical novel in my suitcase. It is a book I convinced her to

write when she was ninety. My idea had been that an autobiography spanning a

century would make interesting reading; I had even suggested a title One

Century, One Life. But when the book was finally written, I realized that

my mother had described mostly the ten idyllic years she spent with my father

before I was born, so the book’s final title became One Love, One Life.

It would now constitute my ultimate card when arguing with the mayor about her

rights to join her husband in their final resting place.

But if nothing worked, I was determined to pay an

Albanian to dig the grave under cover of darkness and secretly put my mother’s

remains where they belonged. “Wouldn’t I love to be there,” responded Carole

when I told her of my intentions.

Agla was alone at the gruesome

process of unearthing our mother’s remains. Agla has often been the one who gets

the snake out of the hole as one Greek proverb goes. Two days later I was

present for receiving the varnished box with the officially disinfected bones.

The man did not let us touch the box. He put it himself in the trunk of Agla’s

37-year old VW beetle. The box would fit under the curved hood only on its

side! Fortunately, it had a locking mechanism. We put no other luggage around

it. We immediately set route for Florina.

We took the

new Egnatia superhighway bypassing the town of Edessa with its picturesque

waterfalls. We were too preoccupied to indulge in touristy sightseeing. While

driving, Agla kept verbalizing her worries. How there were no friends or relatives

of ours left in Florina, whom we could possibly contact for help. And then she

thought of Eleni.

“Eleni may still be there,” she exclaimed.

“Do you know where she lives? Do you

remember her last name?” I asked doubting.

“I can probably locate her house,”

she said, “but in any case, I’m sure people around there will still remember

Socratis.”

Eleni was Fotini’s daughter. Fotini

had been my mother’s helper from the day my mother had children and throughout

our childhood in Florina. She was hard working but very poor, uneducated, and

thankful to my mother for providing work for her. She had three children of her

own (no husband) and they lived in a one-room house at the town’s gypsy-like

quarter with rugs hanging instead of doors. Eleni was a teenager when Agla was

born. The hard years in Florina with long cold winters had resulted in a

bonding between Fotini and my mother, two otherwise incongruent women.

Fotini came to my mother asking for

advice and help with every serious problem she had. One of her early problems

was when Socratis began courting Eleni, eventually seducing her, but refusing

to marry her. My mother’s interventions played a decisive role in Eleni and

Socratis finally getting married. In the decades that followed Eleni had her

own share of hard life: four children, money problems, and an unfaithful

husband who beat her. Finally they all moved to Canada seeking better fortunes,

which they found.

Fotini did not like Canada and frequently returned to

Florina for prolonged vacations. In one such trip, she came to see my mother,

now living in Thessaloniki, with another serious problem. Eleni’s young

daughter in Canada had met a young man who wanted to marry her but there was a

snag. In the tightly-nit immigrant community of Greeks there were rumors that

Eleni’s daughter was not a virgin. The young man refused to believe them

arguing that they were motivated by jealousy. Eleni and Fotini, however, had

good reasons to be worried. When the plans for the wedding began, Fotini came

to my mother for help.

My mother told Fotini that the girl should come to

Thessaloniki as soon as possible. Within a couple of weeks Eleni brought her

daughter to my mother and the three of them went to see a gynecologist in

Thessaloniki. There is nothing illegal about this type of operation and the

gynecologist proved understanding once my mother explained the situation to

him.

Several weeks later a thanking letter from Canada

told about a great wedding that took place, which was coronated the next day by

the display of the wedding sheets stained with blood according to the

custom.

The VW beetle with its odd cargo pulled in Florina

around noon. I was in no mood to go searching for Eleni so we went straight to

the cemetery. It wouldn’t be hard to locate my father’s grave because it is

next to my uncle’s and his mother’s both of which have been decorated with

large marble statues. And yet we couldn’t see my father’s grave! Not only was

it entirely covered by wild bushes growing all over but also there was no

longer a cross with the names on it. We were heartbroken. Moving the bushes I

saw that the cross had broken into several pieces that were scattered around

and the heavy marble plate was darkened with mold stains.

We looked around for help but on Saturday noon the

church was closed. We walked out on the street hoping to find someone connected

with the church. There was an Albanian cutting the grass that grew wild on the

sides of the road.

“Is there anyone from the church around here?” Agla

asked him.

“I don’t no. Church closed,” he said.

“Is there anyone who can help us clean a grave?” Agla

insisted.

“I do it,” he said and immediately stopped what he

was doing, picked up his heavy equipment (chain saw and wire grass cutter, both

gasoline powered) and followed us to the grave.

He worked for half an hour. I gave him ten Euro. He

said nothing and walked away. I gathered all the pieces of the broken cross and

placed them on the marble plate. It looked pathetic.

We went back to town in search of a marble mason.

Minos the marble cutter was a young

man who was obviously taking over his father’s business. He drove with us to

the cemetery, took measurements and jotted down the names to be carved on the

new, heavy-duty cross. He agreed to bring and install the new cross and even to

bring the necessary machinery to clean the marble plate. The only question was

when would the new cross be ready. Tuesday afternoon would be the earliest he

could do it by. We had to agree.

“Actually, we also want to put in

our mothers remains,” I ventured timidly, when I saw him test-lifting the heavy

marble plate.

“That would be no problem,” he

replied, “we can do it Tuesday when I bring the cross.”

“But until then do we drive around

with the bones in the trunk of our car?” Agla objected.

“Oh, you have them here?” He seemed

surprised. “Why don’t you bring them over and we can put them in right now,” he

continued.

That would suit us just fine, I

thought to myself as I rushed to the car.

The

varnished box was actually quite light. As I carried it up the stairs toward

the grave, it crossed my mind that we had not seen what was inside. It would

have been trivial to do it right there because there was no lock on the box’s

locking mechanism, but I had a good excuse: Agla and Minos were waiting for me

to do what we feared would be so problematic, so there was no time to waste.

Minos and

Agla raised the marble plate high enough for me to place the box inside, but

the space underneath was littered with rocks and concrete and I was forced to

lean forward getting my head and shoulders practically inside the grave. As I

struggled to wedge the box in the space available I heard Minos and Agla

talking unable to make out what they were saying. Eventually, I surfaced to

find Minos bursting into laughter as Agla began screaming. In a split second I

realized that Agla’s finger had been caught under the marble plate. “RAISE THE

PLATE,” I shouted at the guy, “don’t you see her finger is caught?”

He complied

embarrassed. Agla’s finger was promising to soon become blue. “I thought she

was laughing at my joke,” he said awkwardly. Apparently when I was half inside

the grave he had winked at Agla making a wisecrack of the sort, “what if we

closed your husband inside!” They also took us for husband and wife with

Grigori our son later at the hotel, even after I specified a room with three

separate beds.

But despite

the mishaps, we felt euphoric. There were no more obstacles in our trip’s

mission and we had three days until Tuesday afternoon to tour the region. Agla

pointed out that we had visited Prespa more than once whereas had never visited

nearby Monastiri our father’s hometown.

Monastiri,

today called Bitola, is the first town across the border from Florina into

FYROM (the Former Yugoslavian Republic of Macedonia). Despite the fact that my

grandfather owned land and boasted the biggest house in Monastiri in early

twentieth century, my grandmother quit the region after her husband’s

assassination. Over the decades the crossing of the border between Florina and

Monastiri saw days of tranquility but also days of high drama and terror. Under

communist Yugoslavia escape stories from Monastiri rivaled those of eastern

Germans striding the Berlin Wall.

Agla’s

suggestion found me cold. I had not been excited to come back to Florina in the

first place, much less to visit a town I had known only through my

grandmother’s stories, many of them in the form of a moiroloï

(dirge). In the local

tradition, at moments of intense self-pity, my grandmother would embark on an

improvised descriptive lamenting recounting all her misfortunes with a fair

amount of detail. How much of this would I be able to crosscheck with a visit

to FYROM’s Bitola today?

Grigori too

had an effective objection. “They’ll stamp my passport with ‘Has been in

Macedonia,’” he complained, “me who has lived in Macedonia all his life.”

Grigori and I would rather go to

Prespa again.

The hotel we stayed at – King

Alexander – was up some way on one of the two mountains that flank Florina. It

commanded a panoramic view of the town and the opposite mountain. It was also

close to the part of town where Eleni’s house used to be.

Following

the afternoon siesta and Greek coffee on the balcony we began asking around for

the house of Eleni and Socratis. A man in his forties who did not entirely

conform to the image of a local volunteered to bring us to where Eleni was. He

brought us to the large two-house complex right across the hotel where we

stayed. The estate was a cross between a spacious summer residence and a farm.

A couple of dogs accompanied us across the yard barking but not menacing. There

were more animals (chicken and geese) at the far end of the long yard. The

young man shouted, “Mom, you have visitors.”

Eleni came

out and looked at the three of us with suspicion.

“It’s me,

Agla, the daughter of Mistress Theodosia,” Agla rushed to clarify.

“My God,”

Eleni exclaimed, “is it really you and Theodorakis?”

I hadn’t

seen Eleni since I was a small child. The woman in front of me bared faint

resemblance to what I had retained in my memory; she also bared the marks of

the passage of difficult times. Despite her eighty years her hair was dyed

black and she maintained a straight posture, but she obviously had false teeth

that moved disconcertingly as she spoke. Her chin trembled intermittently but

not the way it does with old people. My mother had told us that she had had a

nervous breakdown of some sort.

She shouted

at her other son, Giorgos, to come out of the nearby shack. He was in his

undershirt, fat, unshaven, and with a pain on his neck. He looked old. We

pulled some chairs and we all set in a shady part of the yard. They offered us

refreshments.

“When I was

fourteen you were a baby and I was carrying you in my arms,” Eleni told Agla.

“Now I have four children, eight grandchildren, and one great-grandchild,” she

continued contemplatively.

Giorgos

explained to us that with the money he made in Canada he built these two houses

here to reunite the family even though some family, like the younger son Petros

who brought us to Eleni, lived permanently in Canada and came only visiting for

the summer.

We sat

there chatting calmly for a while. There was an atmosphere of harmonious

contradiction. They felt like friends but we hardly knew them; they felt like

relatives but we had nothing in common. What was there to talk about?

Agla made a

remark about the dogs and mentioned her experiences with dogs.

“I had a big

dog once,” picked up Giorgos, “no pure race or anything, which got along

extremely well with the three little kittens of the house. All three of them

slept on him regularly savoring his body warmth. He never complained. One day,

however, the dog must have perceived something suspicious, he suddenly jumped

and ran toward the gate. The three kittens instinctively clawed themselves on

his back. And the dog kept galloping for a long time with the three kittens

wobbling around attached on him. It was hilarious!”

I had my

camera with me and thought of taking pictures but I was afraid it would

embarrass them; or, rather, it would embarrass me. Adjectives like picturesque,

photogenic, or touristy seemed out of place here.

A young

lady and her boyfriend all dressed up came by to meet us as they went out for

an evening ride to Prespa. She was one of Eleni’s granddaughters. I wondered

whether her mother was the one who my mother had fixed up.

We heard a

rooster crow, which prompted Giorgos to tell us another story. “In Canada where

we live peopled complained about the crowing of too many roosters disturbing

their sleep. A law was passed and all henneries were equipped with very low

ceilings. It appears that if a rooster cannot cock himself up, he wont crow!”

“Tomorrow

we are going to have a barbeque. There will be thirty people here. Please come

and join us,” continued Giorgos.

“Oh, yes,

please do,” repeated Eleni and proceeded to elaborate on the invitation and

insist Greek style.

“Mom,”

interrupted her Giorgos, who had obviously been more affected by Canada’s

Anglo-Saxon culture, “stop pestering them. They know we want them to come. They

will, if it suits their program.”

As we

prepared to leave, Petros, who had been very quiet up to then, approached me and

said.

“I live in Vancouver.

I am in the phone book. If you ever find yourself in Canadian soil, no matter

where, give me a ring and I will come pick you up and show you the country.”

We drove

back to the town center somewhat overwhelmed. We had expected to come across no

one we knew in Florina. Passing in front of our old house it now looked sad and

neglected but hanging in there.

We parked

downtown not far from Modis Square. The VW beetle certainly made an impression

in the midst of only modern cars. As I came out of the car in front of a group

of young men drinking summer coffee concoctions, one of them asked me: “would

you sell it?”

“No, it is

part of the family,” I said, “We’ve been growing old together.”

“Where are

you from?” he continued obviously alluding to us looking strangers.

“From right

here,” I responded, “We are from Florina.”

He looked

at us in disbelief. I volunteered a clarification, “The name is Modis.”

“Like the

Modis Square?” he wanted to better understand.

“Exactly,”

I replied.

“Hugh!” he

exclaimed surprised, if anything, at the coincidence of someone being named the

same as a square.

Dinnertime

was approaching and I reiterated my desire to taste once again the famous

soutzoukakia that we used to eat on summer nights in the many tavernas spread

around the central square (not named Modis at that time). The permeating smell

of those sausage-looking spicy meatballs grilled on charcoal is indelibly

imprinted on my sensory memory and is affectionately associated with my childhood

summers.

But now the central square was

surrounded with fancy coffee shops and bars crowded by young ladies exposing

their shoulders and thighs, none of which would be interested in a soutzoukaki.

I even tried sniffing my way toward the delicacy – always emulating how we did

it when I was a child – only to find myself in front of a hotdog-and-hamburger

stand. Disappointed and tired we sat at a rather chic restaurant off the main

street. The waiters, all young men, were untraditionally attentive, polite, and

soft-spoken.

“May I

suggest a local delicacy,” asked one of them as I was reading the menu. “It is

called soutzoukakia and consists of …

“I know

what it is,” I interrupted him. “I’ve been looking for it all over town.”

The next morning

it was Sunday and Agla proposed that we go to the St. George church – now that

we had nothing to fear – and ask a priest to do a trisagio (short

memorial service) on the grave. In preparation I wrote down the three names

George, Theodosia, and Paraskevi on a piece of paper confident that the priest

would not cross check them against the names barely readable on the

broken-cross pieces.

This time

the church was not only open but it was packed with people. We timed it so that

we wouldn’t have to wait long before the mass finishes and we can present the

priest with our request. Working our way toward the priest in the crowded

church Agla bumped on a well-dressed lady. They both burst out with

exclamations.

“Tasitsa!”

“Agla! What

are you doing here?”

“We came to

put our mother’s bones in the grave of our father. And you? I thought you had

moved to Thessaloniki?”

“Our

children live there, but Yorgos wants to finish his days in Florina. He has

retired, of course, but he likes it here.”

Tasitsa was a cousin of ours, whom again I hadn’t

seen for years. Her grandfather and my grandfather were brothers. Her husband

was a gynecologist and his sister had been a colleague and friend of my mother

who enters the picture once again (it must be this trip’s destiny). Back some

sixty years ago my mother had mediated for Tasitsa who lived in Kozani to meet

Yorgos who lived in Florina with the intention to get married; what they called

an arranged marriage. The union turned out successful and they lived happily

ever after in Florina.

Tasitsa was also very religious, knew all the

priests, and when we mentioned the trisagio, she took Agla by the hand and

walked over to the priest.

“Father,

would please do a trisagio for us,” she said and continued on information she

shared with the priest “but you also need to go to that other thing.”

“We can do

the trisagio right here,” answered the priest, “it is the same as if we went to

the grave.”

He

immediately began reciting at a rate so rapid that it seemed miraculous he was

not getting tongue-tied. He suddenly stopped jolting me into reality. He needed

the names. I handed him the paper with the three names and as soon as he read

them Tasitsa added “and Nikolaos and Chrysavgi.” The priest repeated the two

names after her and off he went again continuing his frantic recitation. A few

minutes later there was another pause (obviously he could not read at that

speed) “and Nikolaos and Chrysavgi,” added Tasitsa again and the priest

repeated after her again.

When the

ceremony was over, Tasitsa wanted to go for coffee and I suggested that we

drive to the small coffee shop up the mountain. Driving up the steep mountain

road, five of us in the Volkswagen, we passed in front of a hotel perched on

that picturesque spot.

“This is

the Xenia Hotel,” I said having more memories come to the foreground again.

“No they

have renovated it and renamed it,” Tasitsa brought us up to date. But in my

head I was back in 1974 when Cyprus was invaded by the Turks and Greeks

mobilized for war. We had been vacationing in Greece and had Yorgo baptized.

But in the turmoil and preparations for war between Greece and Turkey my mother

and I came to Florina to seek advice from my uncle George Modis who was old,

retired from politics, and vacationing at this mountain hotel. With all border

crossings closed, one of our ideas was that he shows us the way out of Greece

secretly as he had done so often between Florina and Monastiri when he was

active as a Makedonomachos (Macedonian fighter).

When we met

with him, it was obvious that he was preoccupied with the events in Cyprus. “I

don’t understand,” he kept saying “why couldn’t Greece send some airplanes,

boats, or intervene in some way.”

We hesitated before revealing the

purpose of our trip.

“It is very

easy to cross the boarder,” he said. Then he added as an afterthought, “But for

a Modis to cross the border secretly wouldn’t be right.”

“Yes, of course, Yorgo, you are

right,” said my mother and we dropped the subject.

At the mountain café Tasitsa seemed

to know everyone and be highly respected. The lady café owner greeted her

joyfully and came out to personally wait on us.

“On hot summer days we used to drink

visinada,” I reminisced again. “Do you have it?”

It was a drink made out of black-cherry

syrup. In those days my mother used to make black-cherry blancmange to offer

guests in small quantities with a spoon and a glass of cold water. We children

drained the syrup from the jar and dilute it with water into a summer drink,

dangerously undermining our mother’s ability to play proper host to visitors.

“Of course we do,” said the lady and

brought three of them, one for Agla, one for Grigori, and one for myself.

Later

Tasitsa insisted to invite us for lunch with her husband at a nice new

restaurant they now frequent. She wouldn’t take no for an answer so we made an

appointment for 2:30 pm. She gave us instructions on how to go; we’d all meet

there.

On the way to

the restaurant we stopped by St. Nikolas, the church outside the town diametrically

opposed to St. George. It was a spot where we used to go for picnics with

family but also with the school when I was in elementary school. I distinctly

remembered lots of water even a small waterfall.

Despite

being prepared by now for disappointments, I was taken aback to see the dry

water channels sadly attesting to previous running waters.

My mother

(schoolteacher) 2nd from the right and I centered in primo piano.

I made Agla pose over the spot where

we used to have our picnics.

Agla 3rd

from the right, my mother 3rd from the left,

and I, as

always, centered in front.

The church has been extended with

new structures that hide the fountain, which we did not succeed to see running

anyway.

Agla is the

tall girl waiting to access the water.

The phrase “living color”

popularized when color photography first appeared may be more appropriate as a

euphemism here. The black-and-white pictures are the ones that are full of

life.

Tasitsa’s favorite restaurant consisted of a house

where the owners live and its large garden where the tables are set up in the

shade of the vine arbour. Her husband, Yorgos Lalagiannis, now 88, was the

first gynecologist in Florina where he practiced for many decades. Like most

short people he still sports a Yale chin (always upward).

“I have brought in the world 6,582 babies,” he

boasted.

Thea’s question immediately popped in my mind.

Avoiding the choice between addressing him as “Yorgo” or “Mr. Lalagiannis” I

simply said, “How did women deliver during the war years? Was there a hospital

in Florina?”

“Yes, there was a hospital but it had no maternity

ward. Women simply delivered at home with the help of a midwife.”

“But what about caesarians? You cannot do a caesarian

at home.”

I must have touched a sensitive chord.

“I was the one to perform the first caesarian

operation in Florina in 1956. The inconvenience was we had no anesthesiologists

and therefore performed the caesarians with ether,” he did not want to stop but

I interrupted him.

“But what did women who needed a caesarian do before

1956?”

He continued from where he had left ignoring my

question. “After 1956 we got proper anesthesia and I performed caesarians

routinely at the hospital.”

I came back to my question, “How about when we were

born during the war?”

Before 1956 women could give only natural birth.

Those who didn’t either lost their baby or died.

Lunch lasted for more than a couple of hours. We

talked about relatives and reminisced about old times. Nostalgia reigned in

this mid-summer garden spot. At some point Tasitsa noticed, “There goes Danny

Dosiou.”

I turned around and saw two old ladies slowly leaving

the restaurant holding each other. I grabbed my camera and ran to take a

picture. I gave no explanations but everyone at my table understood my

reaction. Florina is known for its strong cultural tradition. Many of its

inhabitants have excelled both in Greece and abroad as painters, sculptors,

musicians, and singers. Danny Dosiou was a violinist with a brilliant career in

Paris. I know a student violinist from Geneva who came all the way to Florina

just to take private lessons from her.

On the

right Danny Dosiou, an internationally renowned violinist.

When Agla later saw my picture she remarked, “Too bad

you did not take her picture facing you.”

“She is making an exit,” I verbalized my thoughts,

“and a heavier one at that than from the stage.”

In the late afternoon we walked around Florina taking

pictures. As with people, I was again interested only in old “stuff”, buildings

that I would recognize, often in ruins.

The

Peltekis house across the street from ours (Agla is looking at ours).

The two-story house across the street from our house

had an old-fashion coffee shop (Kafenion) on the ground floor frequented

by older men playing backgammon (tavli) all day. It is in there that we

turned for first aid – i.e. ouzo – when I nailed the poor kids leg with my

dart.

On the first floor lived Peltekis, a Greek-army

officer who was hard of hearing. One night during the Greek civil war – after

the Germans had already left – some drunken bandit came knocking on the front

door of our house. My mother and grandmother got really scared because they

lived alone in the house with two small children. My grandmother tried to talk

sense to the bandit from the first-floor window but all in vain. He was shaking

the door threatening to force it open. My mother came out to the balcony and

began crying for help to Peltekis across the street. But she was knocking on

a deaf’s door to quote another Greek proverb! Eventually Peltekis’ wife

woke up and shook her husband into alertness. It did not take him long to get

his pistol, shoot in the air from his balcony, and shout threats to the bandit

he could not see that if he didn’t go away immediately he would come down and

kill him. It was enough to resolve the situation. But my mother the next day

had an iron bar installed reinforcing our front door so that it wouldn’t be so

easy to force open.

Another house with a story was the Tegos’ house. Back

in the 1930s Tegos Sapountzis was the mayor of Florina. He had a beloved daughter Athina,

whom he wanted to give as wife to an aspiring young lawyer, Yorgo Modis, my

father. Athina was impressed by my father and even took the initiative to begin

a correspondence with him. But shy as she was she asked her literary

acquaintance – my mother – for help in writing the letters. My mother even

wrote the letters in her own handwriting, which was particularly artistic. This

made the two young women good friends. So when the big moment came for Athina

to meet Yorgo in the flesh, my mother was not simply invited at the banquet

thrown by the mayor for the occasion but she was also seated next to Yorgo on

the other side. That was it. During the dinner my father paid more attention to

my mother than to Athina.

The Tegos Sapountzis house

Passing by the river in front of my

school I saw a tree where there shouldn’t be one! So I began telling the story

of me coming out of school one day and seeing a bunch of people trying to cut

down an enormous tree. They had cut a wedge on the river side of the tree’s

trunk and were trying to pull the tree down with ropes into the river. The tree

eventually fell but on the other side landing on the roof of a small house. The

owner of the house came out screaming in despair for the damages in her house.

As I was talking in a loud voice, an

older lady close to the house I was pointing at asked, “when were all these

things happening?”

After a moment’s reflection I

answer, “about 55 years ago.”

“Where are you from,” the usual next

question.

“We are from here. Modis is my

name,” the usual answer.

The lady came closer. “Are you the

son of Yorgo and Theodosia Modis?” This time we were recognized!

“Yes, I am,” I answer.

“I had her as a teacher the good

lady,” she continued nostalgically. We chatted for some time and found out

about the whereabouts of many people we new in common.

The tree

(a replacement), the house, and the lady in the red blouse

behind the

car, who was my mother’s student.

One thing I did not want to miss seeing again was the

railroad station. I had fond memories of Florina’s railroad station. My mother

and I used to go there in cold winter evenings to wait for Agla’s coming home

for Christmas and other holidays from Anatolia where she had gone to school two

years ahead of me. Waiting for the invariably late train to arrive, I used to

put my ear on the tracks to detect the coming train ahead of time, as I had

read it was done in books.

It is a remote small-town railroad station whose

particularity is that unlike usual train stations where trains come in one way

and go out the other way, here the access is only on one side. The other side

ends in a mountain: the end of the line.

The tracks

stop here!

The next day, Monday, we began early for our trip to

the Prespa lakes. The region includes two lakes and a large national reserve

rich in bird and vegetation species. The Big Prespa lake is split among Greece,

Albania, and FYROM with the latter claiming the biggest part. Little Prespa is

almost entirely in Greece. The island of St. Achilios in Little Prespa has now

been connected to the shore with a 600-meter long floating bridge. When we

began crossing the bridge, a fisherman just pulled out his nets full with some

enormous fish. He threw them in the trunk of his car still alive in the nets.

“They are going to Kastoria,” he answered the concerned looks on our faces, as

he got in his car and drove away. His remark did not explain why Kastoria,

which has a lake of its own needed all this Grvadi fish from Prespa.

The most striking highlight from our Prespa excursion

was the visit of a remote little church up high in an enormous cave on an inaccessible

shore of Big Prespa. It is the most impressive one of several such shelters

Christian monks sought during the centuries of Ottoman occupation.

One of

several cave shelters.

We hired a boat to visit the caves. The most impressive

cave is not far from the three-border crossing point on the lake. A large

number of steep steps mostly inside the cave brought us to the little church at

the top, which is entirely covered with well-preserved Byzantine frescoes

dating from the middle ages. Coming out of the cave on the way down we were

facing the Albanian coast across the lake.

We came

back to Florina in the afternoon. It was our last evening in town and there

were still a few things we had not visited. Agla wanted to see the old market.

It was still there, right next to nicely renovated Loukas’ house.

Loukas was a pediatrician. He was

also a good friend of our father. He owned much land with chestnut trees. His

wife was stunningly beautiful but they had no children. He was present when

Agla was born, and then again when I was born. On each occasion he had one

large chestnut tree cut and offered as a present to the Modis family. One tree

became a built-in closet and the other one a built-in china cabinet. I remember

both of them distinctly for their dark-color wood.

Loukas’

house (our pediatrician)

As we

walked by his house I asked Agla, “Do you realize we are on another Modis

street?”

Agla knew about the square, of

course, but had forgotten about the street of Captain Modis. He was the brother

of my uncle and had died while fighting the Turks deep in Asia Minor in what

later became known as the Asia-Minor catastrophe of the Greek army.